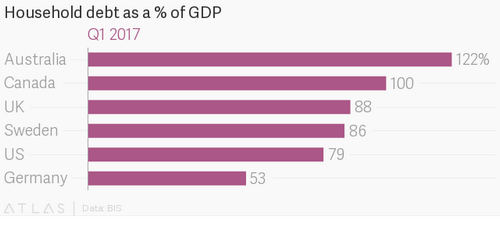

In Sweden, a combination of low interest rates and rapidly rising house prices has been making the central bank nervous for years. House prices have increased by an average of 9% per year for the past three years, pushing up household indebtedness in lockstep.

But now it seems cracks are appearing in Sweden’s housing market, after property prices fell 1.5% in September from the month before and a further 3% in October, some of the steepest declines in years.

Sweden’s central bank is trying to put a positive spin on it. This week, policymakers said the slowdown would lead to a more stable market and, most importantly, limit household indebtedness. “High and rising household indebtedness poses the greatest risk to the Swedish economy”, the Riksbank said (pdf).

Household debts are growing much faster than incomes in Sweden. The average debt-to-income ratio for households with mortgages was 338% in September, up from 326% a year earlier. This makes households vulnerable when interest rates start to rise (the current benchmark rate is below zero, even though economic growth has been relatively strong) or house prices start to fall significantly.

The Scandinavian country doesn’t take the prospect of a housing shock lightly, because it fears a re-run of the early 1990s, when a real estate crash and banking crisis devastated Nordic economies. The central bank warned this week that banks had “major exposures” to the property sector and would be sensitive to a large fall in prices, exacerbated by the fact that local banks are deeply interconnected. Officials are taking measures to engineer a soft landing, including plans to require borrowers to pay off more of the principal on their mortgages and not just the interest.

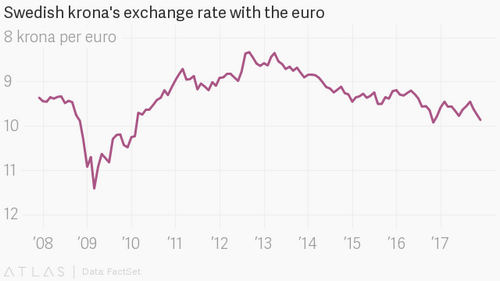

Worries about the housing market are also making traders jittery. This week, the Swedish krona briefly surpassed 10 krona a euro, a level reached only one other time since the financial crisis. At the same time, Sweden’s inflation has started to slow, setting back plans by the central bank to raise interest rates.

If Sweden’s housing market has reached an inflection point, marking the end of an era of low interest rates fueling rapidly rising house prices, other countries should take note. What’s happening there could serve as a preview for places where interest rates have also been low for years and experts fear that housing bubbles have inflated to dangerous levels.

Stockholm and Sydney don’t have that much in common, but as Australia’s housing market balloons to four times the size of GDP, policymakers there should be watching closely to see whether Sweden’s housing market cools in a way that gives over-indebted households time to adjust and the central bank room to raise rates without shocking the system.